Saturday, February 29, 2020

Tuesday, February 18, 2020

Monday, February 17, 2020

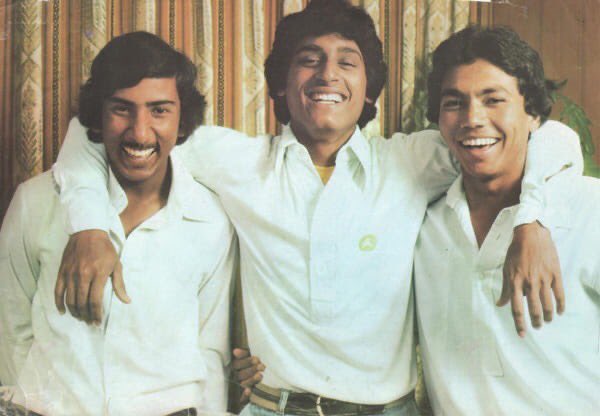

Height of Fashion - Majid Khan, Abdul Qadir and Imran Khan in Late 1970's

Wednesday, January 22, 2020

Thursday, January 16, 2020

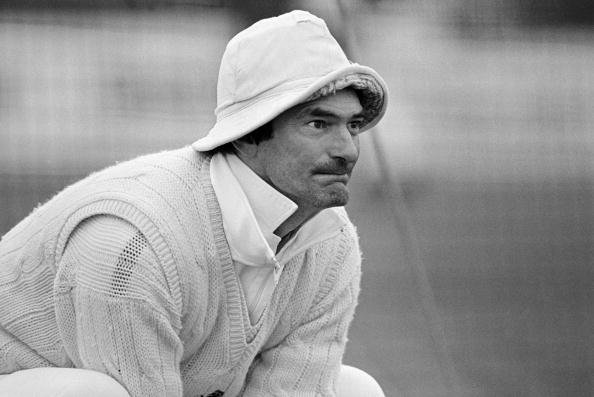

Fred Trueman England 1952–1965

Fred Trueman was not only a great fast bowler, he was also a great entertainer. There is a theatrical element to bowling fast and Fred played it for all it was worth. He’d happily go into the opposition dressing room before play – in a county match if not a Test match. And he announces to the assembled audience which batsmen he’d be getting out later in the day, and how.

You can only really play that game if you have the talent to back it up often, and he did. The fact that he played in an era when television, for the first time, was making stars out of top sportsmen may have helped in the nurturing of the image. But if he was the first to talk himself up, soon enough plenty of others were following suit.

The downside to this was that the black-and-white footage of Trueman in action survived for later generations to scrutinize. Moreover, plenty concluded that he was not quite as fast as the legend. Burnished of course by Fred himself – would have them believe. Make no mistake, though, Fred Trueman was fast in his early days and as time went on. He developed into a highly skillful operator who did not need pace alone to pick up wickets.

In his mature years, he was a highly intelligent operator. He had a lovely action, perfectly honed to the job in hand. You do not become the first bowler in the history of the game to take 300 Test wickets, which Trueman did in 1964, without being very good. His average of 21.57 and strike rate of 49.43 are both exceptional.

The way Trueman burst on to the scene at the age of 21 may have had something to do with how his story unfolded. England had craved a fast bowler of genuine hostility since the days of Harold Larwood. And when in his first match India lost their first four second-innings wickets for no runs, three of them to Trueman.

There was understandable excitement, not least from the bowler himself who sent the Indian batsmen on their way with a few choice words. That, after all, was how a fast bowler was supposed to behave – according to some! Later in the series, Trueman destroyed the Indians in even more comprehensive fashion.

Trueman taking 8 for 31 in a mere 8.4 overs spell. ‘Where would you like the sightscreen, batsman?’ The aura was established but it took Trueman time to adjust to the reputation he had won. On his first England tour to the Caribbean in 1953–54 his immaturity got the better of him as he showed little concern at the way he injured some of the West Indies batsmen.

One of whom was the greatly respected George Headley. He lost his good conduct bonus and played only three Tests in the next three years. The penny dropped in the end and from the time that he got his England place back for an extended run in 1957 he embarked on a golden period in his career.

And the one predicted for him when he first emerged from the South Yorkshire mining community to excite the coaches at Headingly. He took 22 wickets at just over 20 apiece in that summer’s series with West Indies. Which England won 3–0, and he took 15 more at 17.06 against New Zealand the following year.

The realization dawned that a new-ball pairing of Trueman and Brian Statham could be a winning combination. Between May 1957 and May 1963, Trueman took 197 Test wickets and Statham 132. Trueman at the much superior average and strike rate.

Although he had some natural gifts such as strength and speed, by Trueman’s own admission it took him several years to fully master his craft. He learned to pitch the ball up to allow it to swing late. He commanded a big out-swinger but also a deadly off-cutter, as well as a very good Yorker.

Although he became a very canny analyst of conditions as well as the strengths and weaknesses of opponents, there was still the occasional disaster where he lost the plot. When as happened at Headingly in 1964 he tried and spectacularly failed to bounce out Australia’s Peter Burge. It cost England the game.

But against the same opponents on the same ground three years earlier he had bowled brilliantly in victory. For four years from 1959, Trueman was outstanding, taking 20 or more wickets in seven out of eight successive series. Although his overall record in England was exceptional, he was also very good on tours of the West Indies and Australia.

England won in the The Caribbean in 1959–60, which was a terrific achievement given that the West Indies batting included the likes of Garry Sobers and Frank Worrell and came away with a draw – if not the Ashes – in Australia in 1962–63. The one a game that England won in each series owed much to Trueman, who took five for 35 in the first innings in Trinidad and eight wickets in the game at Melbourne.

If Truman’s home and away records are lopsided it is partly because he was selected for so few overseas tours in his early days. That said, his figures in England accurately reflected how dangerous he was when the ball moved around: he took 229 wickets at home at a shade over 20 each and a strike rate of 44.9.

Jim Laker and Tony Lock took their Test wickets in England more cheaply but none of England’s leading bowlers can improve on Trueman’s strike rate in home matches. Not until James Anderson overtook him in 2014 did anyone beat his haul of wickets in England.

After retirement, Fred Trueman almost became a caricature of himself, whether as a radio summarizer or as a regular voice on the after-dinner circuit. He was disappointed at some of the things that might have been – he would have liked the Yorkshire captaincy, but it never came his way – and decried what he saw as declining standards.

In truth, he was never quite the character of popular myth. He was not a big drinker, nor really a fire-breathing monster. But it had served to think he was. As John Warr, another England bowler once said of Trueman, ‘Cricket and the Anglo-Saxon the tongue has been enriched by his presence.’

Monday, December 30, 2019

Sir Garfield Sobers - One of Five Wisden Cricketer of 20th Century

Many cricketers have declared him the true legend of Cricket and he remained a hero of modern cricketers as well. This guy was so special when in full mood. Garry Sobers minimal foot movement, great follow-through, the ball ricocheting off the boundary boards as not a man moved. The way he moved was magical; a lithe, lissome, loose-limbed creature. Just to be able to carry off the whole thing must have been a triumph.

His epic innings for a World XI against Australia at the MCG at New Year in 1972, when he was at full mood by scoring 254 of the finest runs you will ever see. He was a genius at work against some of the best bowlers in the world. It was described by Bradman as ‘probably the greatest exhibition of batting ever seen in Australia’.

Garry Sobers was the supreme all-rounder, an almost mythical figure who could bat, bowl quick, bowl swing, bowl cutters, bowl spin, catch pigeons, play golf and of course famously carouse. You would not recommend to a young player today all aspects of his self-confessed love of life. The gambling has obviously been a bit of an issue for him – but if he was a little bit late of a night, he felt he owed his teammates a good performance the next day.

So, perhaps that side of things did not do his game any harm. His 26th and last Test century against England at Lord’s in 1973 was apparently scored after a night on the tiles. In contrast to today’s hard-headed world where winning and stats are everything. There was a certain romance about the way he played to entertain.

Of course, this did not always work out to his advantage – there was that infamous declaration against Colin Cowdrey’s England team at Port of Spain in March 1968, which cost West Indies the match and ultimately the series – but the game was better for it. In the balcony, he was frustrated all alone and Caribbean press rated the declaration as a war criminal.

It was entirely appropriate that he should be the first man in the history of the first-class game to hit six sixes in an over. Therefore, on 31 August 1968, he smashed six sixes to Malcom Nash. Has there been a more versatile or natural cricketer? His status as the greatest ever Test all-rounder is rarely if ever questioned. Jacques Kallis’s figures bear comparison but Sobers was more of a front-line bowler and more capable of winning a match.

For most of his a career he would have been worth picking as batsman or bowler. There was nothing negative about his play. He didn’t use pad-play and he ‘walked’ if he knew he was out. Bradman said he saw no one hit the ball harder. He was largely untroubled by the best and fastest bowlers of his day – Ray Lindwall, Keith Miller, Fred Trueman. You name them – and even in an era before helmets he wasn’t in the habit of being hit on the hands or the body.

He was largely uncoached. Born in humble circumstances in Barbados, he was brought up as one of seven children by his widowed mother. When he was five, his father having been killed in the war while serving on a merchantman that was torpedoed in 1942. Moreover, one of his brothers died with an accident with a Kerosene lamp. His brave mother strongly holds the family, and hence, 14 years old Garry was a gopher in a furniture factory. That trouble days could not de-motivate him to playing cricket.

Even so, he was playing for West Indies by the age of 17, chosen initially as a left-arm a spinner who batted low in the order; just four years later, having moved up to number 3, he was breaking the world Test record by scoring an unbeaten 365 against Pakistan at Kingston, Jamaica. True, the bowling was not the toughest, but then nor had he previously scored a hundred for West Indies.

When Garfield Sober's record eventually fell, to Brian Lara in Antigua in 1994, he was on hand to witness the handing over of the baton to his young protégé. It is hard to imagine that he could ever have played differently to the way he did. But he was profoundly affected by the death of his West Indies teammate Collie Smith in a car accident in 1959 when Sobers was at the wheel.

‘In all my innings, I played with him inside me,’ Sobers said. These days, cricketers are used to the idea of playing all year-round, but it was less common before air travel made the world a smaller place. Garry Sobers was among the earliest jet-age players and throughout his pomp, he maintained an amazingly full schedule.

A cricketing genius played domestically with great success in England for Lancashire League teams. And later for Nottinghamshire, and for South Australia in the Sheffield Shield, all the while continuing to perform for Barbados and West Indies. Of course, his body felt the burden in the end. But he was naturally fit and amazingly did not miss a Test match between 1955 and 1972.

His record against England was astonishing. In 36 Tests against them, he scored 3,214 runs at an average of 60.64 and took 102 wickets at 32.57, as well as 40 catches that he would have taken with minimum effort. His performances in the 1966 series in England must rank among the finest of all time: 722 runs, 20 wickets and 10 catches. But he also averaged more with the bat than the ball. Which has always been one of the best measures of an all-rounder’s worth – against both Australia and India.

At the time of his retirement in 1975 – the year he was knighted by the Queen at Barbados Garrison Racecourse. His career tally of 8,032 runs in official Tests had not been better but that haul takes no account of the many runs he also scored in matches for the Rest of the World against England in 1970 and Australia in 1971–72 that ranked as Tests in all but name.

Indeed, for several years England matches counted in the Test records before being reclassified on the insistence of the game’s rulers. His regrets must be that he missed out on the riches the modern game has had to offer. Just imagine how much he would fetch in an IPL auction – and that, after taking over from Worrell, West Indies did not really progress under his captaincy.

Although he was hardly the only great player for whom leadership did not work out. Garry Sobers had little enthusiasm for the politics that motivated many West Indies players. Some of whom he disappointed by visiting Rhodesia and not criticizing the Caribbean rebels that toured apartheid, South Africa. He has numerous cricketing achievements. In 1964, he was declared Wisden Cricketer of the Year. Then in 2000, he was selected as one of five Wisden Cricketers of the Century.

Overall, he played 383 first-class matches, in which he scored 28,314 at 54.87 with 86 hundred, 121 fifties, 407 catches, including career-best 365* against Pakistan. Moreover, his bowling stats in first-class cricket is very impressive as well, by getting 1043 wickets at 27.74 with the best of 9 for 49, including 36 times five wickets in an inning and one time 10 wickets in a match. These stats clearly show, how was he truly legend cricketer.

Saturday, December 28, 2019

Alan Knott England 1967–81

Alan Knott was born on 9 April 1946 at Belvedere, Kent. He was a former wicket-keeper batsman who represented England at the international level in both Tests and ODI. Alan Knot made his Test debut at the age of 21 against Pakistan at Nottingham which England won by 10 wickets. He took 7 catches (3 in first innings, and 4 in Second innings) in the match and Mushtaq Muhammad dismissed him on Zero.

Philip Eric Knott was one of the purest eccentric wicket keepers there can ever have been. He played alongside many great England cricketers. But many saw him enough for over the years. He was a teammate, opponent or simply observing him on TV, to get the very real sense of a genius at work.

His departure for World Series Cricket opened a door into the England team for Bob Taylor, with whom he played many times, and Taylor’s own class as a glove-man was itself a clue as to the quality of the man who had been referred to him year after year.

Alan Knott superior batting played a part in this; as keepers, they were both outstanding. It would feel wrong not to include someone in a list of this sort who was a specialist wicket keeper as opposed to those such as Adam Gilchrist, Kumar Sangakkara and AB de Villiers who, fine keepers though they were or are, were chosen for their sides as much if not more for their batting skills.

Alan Knott had the silkiest of hands. People often say that you only notice a wicket keeper when he is doing things wrong and, on that basis, it was easy to overlook how well Knott was doing his job. Keeping wicket standing back to fast bowlers and standing up to the stumps for spinners are very different tasks, but his technique and movement were always excellent.

The ball just seemed to nestle into his hands every time he took it. Many remember him taking a catch off quite a thick edge while standing up to a left-arm spinner. Probably Derek Underwood, with whom he formed a great alliance. His hands just seemed to glide into the right position, and you were left wondering how on earth he could have reacted so quickly.

Very few keepers would have held that catch; most would have seen the ball clatter off their wrist. Keeping does not get any better than that. Taylor ran him close, so many cricketers feel privileged to have played alongside both. As a talented wicket keeper sometimes are, Alan Knott was a complete eccentric, but only bonkers in an endearing rather than an irritating way.

Concentrating intently on every ball that is bowled for hour after hour probably encourages a certain quirkiness and fastidiousness; they feel everything must be just right if they are not to commit the inexplicable, costly error. One of Knott’s obsessions were keeping himself ultra-fit, this at a time when fitness was not quite the prerequisite for England selection that it is now.

Like Jack Russell – another member of the wicket keeping fraternity with oddball tendencies – Knotty looked a bit of a shambles in his beloved floppy white hat, but you hardly cared about that when the ball went so precisely and regularly into the gloves. He was born to his work. He established himself as Kent’s regular keeper at the age of 18 and having been chosen for his first Test at 21 cemented himself as England’s first-choice glove-man within months, excelling on his first winter tour of West Indies under his Kent colleague Colin Cowdrey in 1967– 68.

England had been through several keepers in a previous couple of years and we're grateful for the stability Knott offered. He became a central figure in a highly successful England Test side in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and helped Kent win multiple championship titles and one-day trophies. He was also a very gutsy, pugnacious batsman who made a specialty of digging England out of trouble in a resourceful, unorthodox fashion.

His strengths as a keeper were his massive strengths as a batsman too. His agility and quick-footedness made him nimble around the crease and therefore difficult to bowl to. His ability to concentrate for long periods and watch the ball closely helped not only when he was standing behind the stumps but when he was in front of them too.

It was a great a testament to his batting skills that he coped better than most of England’s specialist batsmen with the raw pace of Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson in Australia in 1974–75. Only Dennis Amiss scored more runs for England in that series; a defiant century at Adelaide was one of five three-figure scorers Knott made in Tests.

He may have used unusual methods at times, but he would not have scored the runs he did in that series – with no helmet for protection in those days, of course – had he not possessed a fundamentally sound technique. He also took another century off Australia is a famous partnership with Geoff Boycott at Trent Bridge in 1977 when they rescued England from a desperate start that had seen Derek Randall fall victim to Boycott’s famously erratic running between the wickets.

In 95 Tests he scored 30 half-centuries in addition to his five hundred, which suggests impressive reliability. In later times, keepers were expected to offer more with the bat then they were then, but his Test record of 4,389 runs at an average of 32.75 put him in the all-rounder class for his generation.

He finished with what was then a Test record of 269 dismissals, which would have been many more had he did not sign up with Kerry Packer and for a rebel tour of South Africa, decisions that meant he appeared in only six Tests after 1977. He was only 35 at the time of his last Test and could easily have kept going for a few years beyond that.

A renown cricket journalist Simon Wilde describes him "a natural glove man, beautifully economical in his movements and armed with tremendous powers of concentration". Hist test career was ended against Australia at The Oval, the 6th match of the Ashes series in 1981. He scored extraordinarily 70 not out innings that save the match.

Alan Knott was born on 9 April 1946 at Belvedere, Kent. He was a former wicket-keeper batsman who represented England at both level in Tests and ODI.[/caption]

Alan Knott was born on 9 April 1946 at Belvedere, Kent. He was a former wicket-keeper batsman who represented England at both level in Tests and ODI.[/caption]Read More

- Ben Hollioake – A Star Which Could Not Shine

- Ian Botham England Greatest Ever All Rounder

- Brian Statham – Modest Background was True Great

- Colin Cowdrey – First Batsmen to Play 100 Tests

- Jack Hobbs – First Professional Cricketer to be Knighted

- Jim Laker – 19 for 90 A Unsurpassable Feat

- Jim McConnon – England Right Arm Off Spin Bowler

- Brian Luckhurst – A Dependable English Batsman

- David Sheppard – A Tall, Graceful off Side Batsman

- 50,000 Runs in all forms of cricket

- Wally Hammond ! England Giant Batsman 1927–1947

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)